Sex in two worlds: A Middle Eastern perspective on intimacy

By Colleen Jennings

If you are from a Western country, you probably have never stopped to consider the amount of contact you have with the opposite sex throughout the course of your daily life. You went to school with boys and girls and spent all your days with friends and family members of both sexes. Sex, and the understanding of it, is flavored by each of these experiences and encounters. However, if you grew up in the Middle East sex no longer looks the same, as contact with members of the opposite sex was most likely severely limited. How does understanding this perspective offer our more open culture insight into improving the quality of the sexual experiences?

In most Middle Eastern countries—but particularly in the more conservative, wealthy Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Oman—contact with the opposite sex is limited to parents, siblings, and younger children (Singerman, 2007). Marriages are arranged by families, and most couples have only a few meetings before the wedding, and then only in the company of their parents or guardians. Imagine the wedding night and the consummation of the marriage—two people coming together who have never experienced or observed public physical contact with a member of the opposite sex, much less intimate sexual contact!

As Middle East values collide with those of the West in this age of global communication, morality is refined and redefined for and by a new generation. However, what does this conservative Middle Eastern perspective offer the West? Perhaps better understanding of their traditions can help us better navigate our relationship with members of the opposite sex.

The value of virginity

With the institution of the bride price in existence for centuries in the Middle East, combined with sharia law requirements regarding premarital sex and adultery, the woman’s virginity is her main identity and source of value until and after marriage (Ali, 2010). The

Since a considerable amount of wealth is exchanged in bride-price transactions, a Muslim woman’s virginity is a source of intense interest among family members and the community at large (Huber, 2011). A suitable candidate will be selected from a closely-connected family, possibly even a cousin, and the groom is usually much older than the bride. This age differences is a cause for anxiety among Western observers who prefer more equitable ages between marriage partners (Abdallah, 2009).

In modern circles, however, couples are more age-appropriately matched, for better or worse. It should be kept in mind, however, that younger men are kept at a disadvantage in our current extended global economic downturn (Singerman, 2007). Men are expected to not only pay the bride price, but be prepared to be the sole provider, even in modern marriages. Although families are very interconnected and provide substantial ongoing support for couples, fiscal accountability can keep many young Arab men frustratingly unmarried and without sex often until their late 20’s or early 30’s.

Although this is not dissimilar to Western men, who often do not marry until at least this age, the difference is in the lack of sexual encounters available to men in the Middle East.

Social media and sex

Although the topic of sex in this culture is quite taboo and people rarely share their thoughts, dating is observable. Quite a different phenomenon than Westerners are used to, dating usually happens via Facebook posting, where in a game of counter-posting on topics of interest occasionally young people may take the risk of directly messaging someone.

Engaging in social media communication puts the reputation of young women at risk, however. I have followed the conversation strands of many Iraqi youth—mostly young men in their mid-twenties—as they debate the traditional and changing morals extensively among themselves. A girl can have her reputation and suitability for marriage severely damaged or destroyed if someone posts even a fully-clothed, normal picture of her on Facebook. If she is with a male person who is not her relative in the picture, her reputation is most certainly finished.

This offers quite a comparison to Western culture where much is shared on social media from a very young age. It also offers an opportunity to explore the significance that liberally posting information and images has on one’s reputation, even in a more open culture such as ours.

After the consummation

In the Middle East, emphasis is placed on determining appropriate behaviors leading up to marriage. After the wedding; however, all discussion goes deathly silent. Christian women in Middle Eastern countries will appear on Facebook, but Muslim women—who were barely seen or heard from before marriage—are even more obscure after marriage. This makes an equitable discussion about sex impossible, leaving much to speculation and inference.

The West struggles with the idea that sex can be pleasurable within the context of marriage, often preferring to frame illicit sex as more dangerous and therefore more exciting and satisfying than marital sex (Vrangalova, 2014). Under current Western feminist standards, one might might seek to portray Middle Eastern women—especially younger brides—as victims within the marriage, serving only to gratify the needs of the male spouse.

The real question becomes: how enjoyable is sex for the man and the woman, and does that pleasure factor change over time? In bride price cases, Westerners must be careful not to project ideas of sexual freedom as prerequisites for sexual pleasure.

The landscape of marital intimacy

Since almost no research is available on this topic, what can we conclude about sex among men and women in Middle Eastern countries based on empirical observations? We can imagine a private place where the deeper mysteries of love are explored within the safety of a loving relationship, or we can envision a strained relationship where needs are not being met, but for the sake of honor, never brought up or discussed.

Are Muslim or any women in the Middle East more submissive to their husband’s needs, perhaps, than a Western woman might be? Does a Western woman exert her will and preferences more in the sexual relationship? If so, how does that affect the interpersonal relationships comparatively of couples? Are men trained to be more, or less, sensitive toward women’s issues within the relationship? In the end, does the satisfaction of each person depend more on the kindness and stability of their partner and themselves than on the dictates of their cultural institutions?

Embracing the western experience of intimacy through a middle-eastern lens

In Western society, where cultural pressures toward sex in marriage are less restrictive, and yet men and women seek to fulfill their basic relational need for intimacy in a way that is meaningful for them, it might be helpful to consider the care Middle Easterners put into planning and preparing for one of life’s most special moments.

If you are already in a relationship, regardless of your level of satisfaction, imagine your relationship as the one everyone around you imagined and arranged and put so much interest into. How will you treat your special partner at every encounter? Imagine you can have no contact with someone of the opposite sex, only this one, and consider how that changes your perception of intimate contact.

Take some time to digest the differences in culture you have learned and perhaps explore a bit more what similarities we might share.

Works Cited

Abdallah, S. L. (2009). Fragile intimacies: marriage and love in the Palestinian camps of Jordan (1948-2001). Journal Of Palestine Studies, 38(4), pp. 47-62. Retrieved April 10, 2016

Ali, K. (2010). Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam. USA: President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Huber, B. R. (2011). Material Resource Investments At Marriage: Evolutionary, Social, And Ecological Perspectives. Ethnology(50.4), 281-304. Retrieved from Academic Search Premier. Web. 15 Nov. 2014. http://0-search.ebsco

Singerman, D. (2007). The economic imperatives of marriage: Emerging practices and identities among youth in the Middle East. Middle East Youth Initiative Working Paper.

Vrangalova, Z. (2014, April 25). Is Casual Sex on the Rise in America? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/strictly-casual/201404/is-casual-sex-the-rise-in-america

Colleen Jennings is a “choice” educator of five children, all nearly grown, that focuses on alternative education methods for refugee children in the Middle East. She is completing a master’s degree in political science and beginning another in international education. She continues her socio-political research through her growing social network locally in Colorado and through visits and social media in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey.

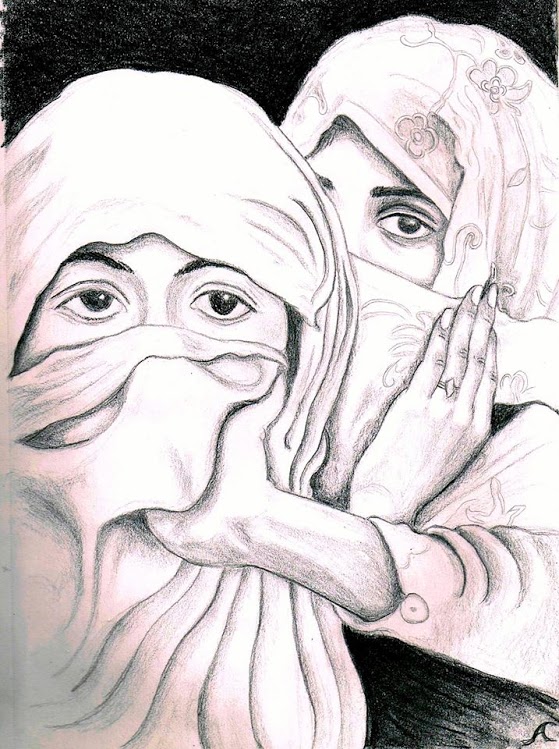

sex is not an open topic of conversation in the Middle East, but this may not necessarily be a bad thing. art by Alma Carel

sex is not an open topic of conversation in the Middle East, but this may not necessarily be a bad thing. art by Alma Carel  sex is not an open topic of conversation in the Middle East, but this may not necessarily be a bad thing. art by Alma Carel

sex is not an open topic of conversation in the Middle East, but this may not necessarily be a bad thing. art by Alma Carel